Have Property Damage?

Call Us 800-345-8321

Insurance May Not Ensure a Home's Replacement

By SUSAN B. GARLAND

3/23/03 - New York Times

LITTLE more than a year ago, a wildfire destroyed the 2,250-square-foot house that Robert and Ann Burton owned in Fallbrook, Calif., about an hour north of San Diego. The loss of their home, along with 42 other houses in the area, was devastating enough. But the Burtons said they also had to deal with another shock: their homeowner's insurance policy did not cover the full cost of rebuilding.

LITTLE more than a year ago, a wildfire destroyed the 2,250-square-foot house that Robert and Ann Burton owned in Fallbrook, Calif., about an hour north of San Diego. The loss of their home, along with 42 other houses in the area, was devastating enough. But the Burtons said they also had to deal with another shock: their homeowner's insurance policy did not cover the full cost of rebuilding.

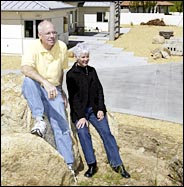

"We trusted the agent to know what the house would be worth," said Mr. Burton, 63, a retired director of student activities at the local high school. Only two years earlier, he and Mrs. Burton, 58, a retired teacher, had moved into the home, which overlooks miles of avocado groves.

Many homeowners are under the impression that their insurance will pay the full cost of replacement if their houses sustain extensive damage from fire or other causes. Yet three-quarters of all homes nationwide are undervalued for insurance purposes, by an average of 35 percent, according to a study last year by Marshall & Swift/Boeckh, a firm based in New Berlin, Wis., that provides building cost data to the insurance, construction and appraisal industries.

In recent years, rising construction costs and property values have increased the cost of replacing a home. From 1996 to 2002, the cost of building a home rose 28 percent in the Northeast and 33 percent in the West, according to the Census Bureau.

Over the same period, many insurance companies, stung by big losses on homeowner policies in the 1990's (in part because of hurricane and wildfire claims), have dropped "guaranteed replacement cost" coverage. In those types of plans, the insurer promises to pay the full cost of restoring a home to its original condition. But such plans do not cover the home's contents.

Most new policies make homeowners responsible for seeing that their coverage reflects rising market values and keeps pace with increases in rebuilding costs. But homeowners often don't realize that.

"So many times, consumers first get their policies when they buy their house, and they don't consider that the replacement and market values of their homes can go up substantially over time," said Madelyn H. Flannagan, a vice president of the Independent Insurance Agents and Brokers of America, based in Alexandria, Va.

These days, most companies offer "extended replacement" instead of guaranteed replacement coverage. These policies insure the home for a specific value, and usually add a 20 percent to 25 percent cushion - or extended limit - if reconstruction costs run over. The policies also provide for the loss of contents, covering them at 50 to 75 percent of the value of the home. In addition, insurance companies often include annual adjustments for inflation, in recent years around 2 to 3 percent.

But that may not be enough. Increases in construction costs in a given housing market could far exceed inflation provisions.

The Burtons said they had a bigger extended limit, of 50 percent, on their house. After the fire, Mr. Burton said, a builder who was recommended by the Allstate Insurance Company, his insurer, came in with a reconstruction estimate that was nearly $70,000 more than the policy value, including the 50 percent cushion, that was set by the agent. Mrs. Burton said that the insurer refused to pay anything more than the value stated in the policy, including the cushion, and the couple accepted the decision. Later, she said, representatives from the California Department of Insurance, meeting with some Fallbrook homeowners who also contended that their coverage had fallen short, suggested that their carriers could be accountable if they portrayed themselves as experts in valuing a home.

The Burtons and many of their neighbors filed complaints with the insurance department. The couple also filed a lawsuit in November in State Superior Court in San Diego County against Allstate and its agent, contending negligence and fraud. The case, which has been moved to federal court at Allstate's request, is pending, according to Robert J. Wolfe, a lawyer at the Los Angeles firm of Engstrom, Lipscomb & Lack, who is representing the Burtons.

An Allstate spokeswoman, Emily Daly, said it was company policy not to comment on pending litigation. But she said that the company "uses tools that determine that limits are set properly."

The Burtons, meanwhile, said they moved into a nearby condominium for a year and are now staying at a friend's guest house while they wait for their home to be rebuilt. The house, Mr. Burton said, will have the same total square feet as the original home, though without some of its features, like exposed wood beams. He says they will have to spend about $80,000 out of pocket to cover all the rebuilding and landscaping costs.

Robert W. Crine Jr., the president of Marshall & Swift/Boeckh, said insurers have traditionally used a square-foot measurement to set home values, without taking into account cost differences in housing materials - plaster versus drywall, for example - and amenities like solid wood floors. He added that more insurance companies, though, were turning to "total component estimating," which analyzes all features of a house, from roofing materials to bathroom tiles. "The system then prices out each characteristic individually," said Mr. Crine, whose company has developed total-component technology for the insurance industry.

Homeowners whose insurers do not use this technology have other options. On their own, they can hire a contractor, an appraiser or an expert in repairing building damage to review all the details of a house and come up with an estimated cost for replacement. A policyholder should consider switching companies, experts say, if the insurer refuses to consider that estimate or insists on a less effective way of setting values, like the square-foot method.

A handful of companies, including Chubb and Fireman's Fund, still offer guaranteed full-replacement policies. Mary Ann Avnet, the vice president for personal insurance at Chubb, said such coverage from Chubb costs about 15 percent more than standard policies, and is aimed mainly at custom homes. Chubb has its own appraisers who inspect each house covered by such a policy, talk to local builders to determine construction costs and set premiums based on that information, she said.

Homeowners should not confuse property value with replacement costs. If houses in a neighborhood are selling for $500,000, the cost to rebuild a particular house could be more or less, depending on construction costs in the area. And policyholders should make sure that they are not insuring the value of the land, which usually runs about 25 percent of the average home price, according to Ms. Flannagan of the independent insurance agents' group. She advises homeowners to check their tax assessments for the breakdown of land and house values. Homeowners do need coverage, though, for landscaping and for debris removal costs, Ms. Avnet added.

Policyholders also need to notify their insurance companies when they renovate. Nearly 60 percent of homeowners who make major structural changes, like remodeling baths or kitchens, fail to update their policies, according to the independent agents' group. Yet, the organization said, one in four remodeling projects increases the value of the home by more than 25 percent.

"Even if I'm only installing new granite counter tops, I would call my agent," said P. J. Crowley, a vice president of the Insurance Information Institute, a trade group. "Over time, making improvements of even several thousand dollars can quickly bring you over the limit."

Local building codes and ordinances should be considered, too. If your house is severely damaged, the local government will probably require you to meet codes for electrical wiring, plumbing and other fixtures when you rebuild. In many cases, homeowner's policies do not cover the extra expense of rebuilding to code unless the policy includes an "ordinance and law" rider.

Jos� Gonzales and Mary Linnerooth Gonzales learned that the hard way last year, when a spark from a welder that Mr. Gonzales was using in a home improvement project ignited a trash can filled with dryer lint. The house, in Silver Spring, Md., was owned by Mr. Gonzales's parents, who do not live there. The couple escaped the fire unharmed, but the house, 100 years old and with two bedrooms, was severely damaged.

Mrs. Gonzales said that during the 30 years her in-laws owned the house, their insurance carrier never advised them to buy insurance that would cover the expenses of meeting updated building codes. She said that the insurance company would not pay for the upgrades of wiring, plumbing and structural repairs, which are expected to cost around $12,000, though the couple were still negotiating with the company. "You depend on the insurance company to tell about these things," said Mrs. Gonzales, 28, who works as a nanny.

It is not unusual to have gaps in home insurance coverage. Policies may exclude damage from the backup of sewers and drains, although such coverage is available at an extra charge. The best way to become aware of what is and is not covered is to read a policy's fine print.

Of course, insuring for full replacement or adding riders raises premiums. As it is, the cost of the average homeowner policy is expected to rise 9 percent this year, after an 8 percent increase in 2002, according to the Insurance Information Institute. But instead of reducing coverage, Mr. Crowley advised, homeowners may want to raise the deductible. By increasing the deductible to $1,000 from zero, he said, a homeowner may save up to 25 percent on the premium.